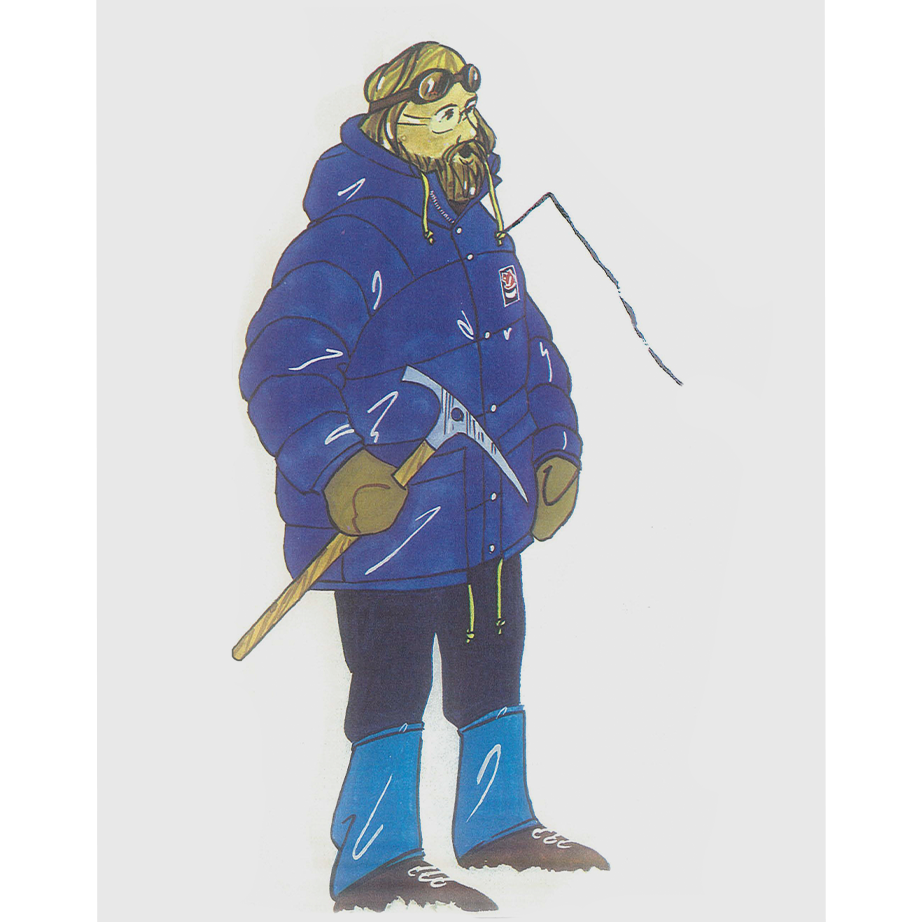

1974 – Åke decides to never feel cold again

Åke Nordin, founder of Fjällräven didn’t know he was about to create the legendary Expedition Down Jacket. He just wanted a way for his teeth to stop chattering.

OUR HISTORY | 7 minutes read

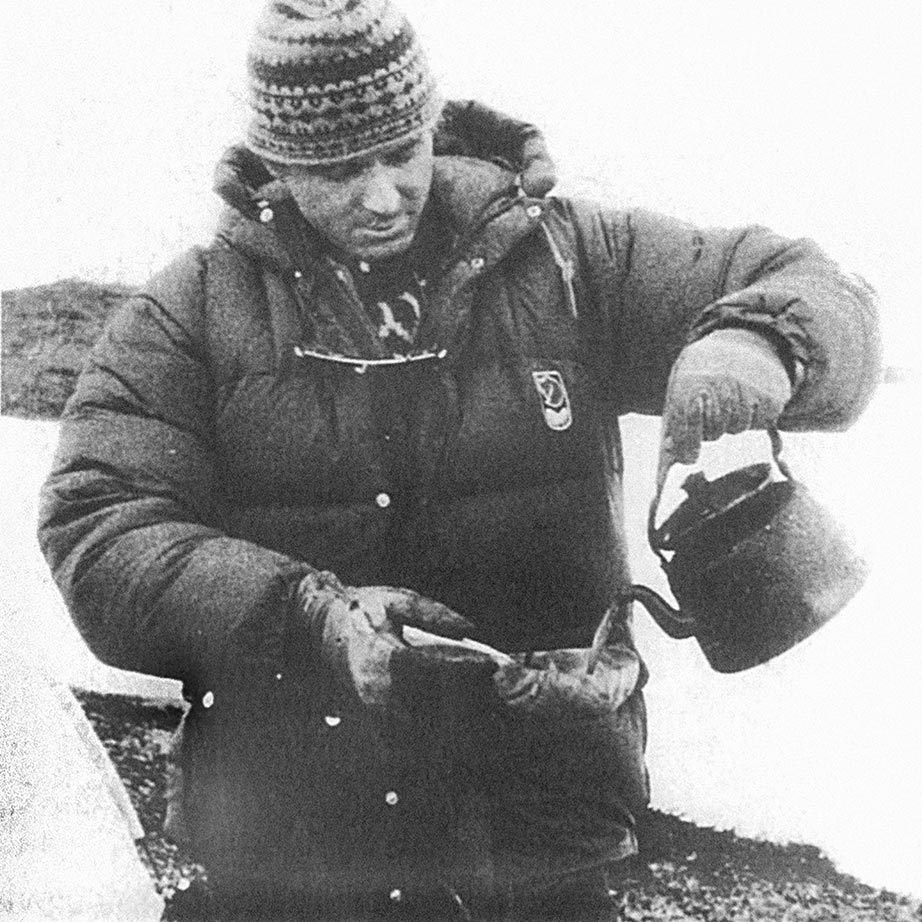

Necessity is often the mother of invention. Fjällräven’s founder, Åke Nordin, was in a bivouac – basically a pit in the snow – on the barren mountain plateau of Abisko in Sweden’s far north, enduring an unbearably cold and windy night.

Bitter cold was Åke’s least favourite aspect of outdoor life. He lay there freezing, his teeth chattering, and began wondering if perhaps he could invent a jacket in which it was impossible to freeze.

Åke had long hated the army’s unpleasant sheepskins, which quickly became wet and heavy to wear. He imagined a lighter garment that could be compressed to occupy less space in the backpack and when worn could insulate at pretty much any temperature.

Two down jackets, sewn together into one, were the product of that cold and windy night 300 km inside the Arctic Circle.

Learning from the best is a good start

Learning from the best is a good start Back in 1940, an American named Eddie Bauer patented the pattern for the world’s first down jacket after catching pneumonia during a fishing trip in the US state of Washington. His down-insulated parkas were a preferred choice for US combat pilots, who flew in them in World War II.

Åke had always learnt by dealing with people who were more skilled than himself.

The down insulation experts were in the US, so that’s where he headed. At an outdoor fair in Chicago he met the rock climber George Lamb, founder of Camp 7 – at the time one of America’s foremost manufacturers of down jackets and sleeping bags.

Lamb sold his business a few years later to a Californian company and retired to take care of his horses, but not before taking his Swedish friend to Boulder, Colorado, to teach him how best to develop his own insulating down jackets, and other products, such as sleeping bags.

In those days, the pioneers of the outdoor equipment industry were primarily self-taught outdoor enthusiasts. All would help each other with new inventions and solutions. Just as Lamb shared his knowledge, Åke published the drawings for his revolutionary Thermo tent in Fjällräven catalogues so that people could attempt to refine the design. On his return to Örnsköldsvik, Åke finally had the tools he needed to design a functional garment that stopped the wearer from freezing. Sitting at his Singer, he sewed a jacket of durable Rutarme polyamide (nylon) fabric comprising a smaller jacket inside a larger one.

Fjällräven Expedition Down

US army tests had shown a ten-centimetre-thick layer to be capable of insulating down to minus 40°c, provided air ducts are sewn in the space between the inner and outer jackets, as in a sleeping bag.

With this knowledge and using the technique he’d learnt in Colorado, Åke filled these ducts with goose down and feathers but packed the shoulders with a layer of Dacron polyester fibre to prevent them from compressing and losing insulation when wearers carried heavy tools in their pockets. He fitted the jacket with an insulating hood that covered everything but the eyes when pulled tight, and he made the garment long enough to cover the wearer’s bottom.

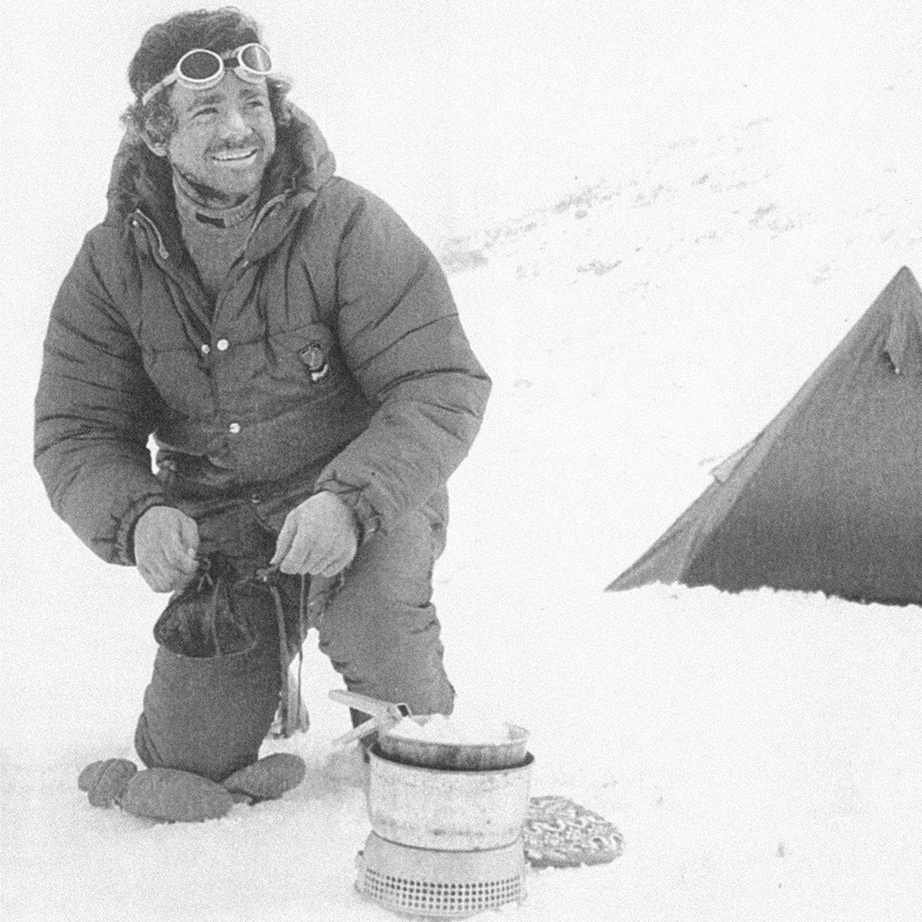

After testing his prototype carefully, Åke began producing the Fjällräven Expedition Down Jacket in 1974. The hood came with yellow waxed strings of the same durable type as in ice hockey boot laces. It was a jacket that kept the wearer warm in extreme temperatures in places with no indoor shelter.

From the South Pole to the streets of Stockholm

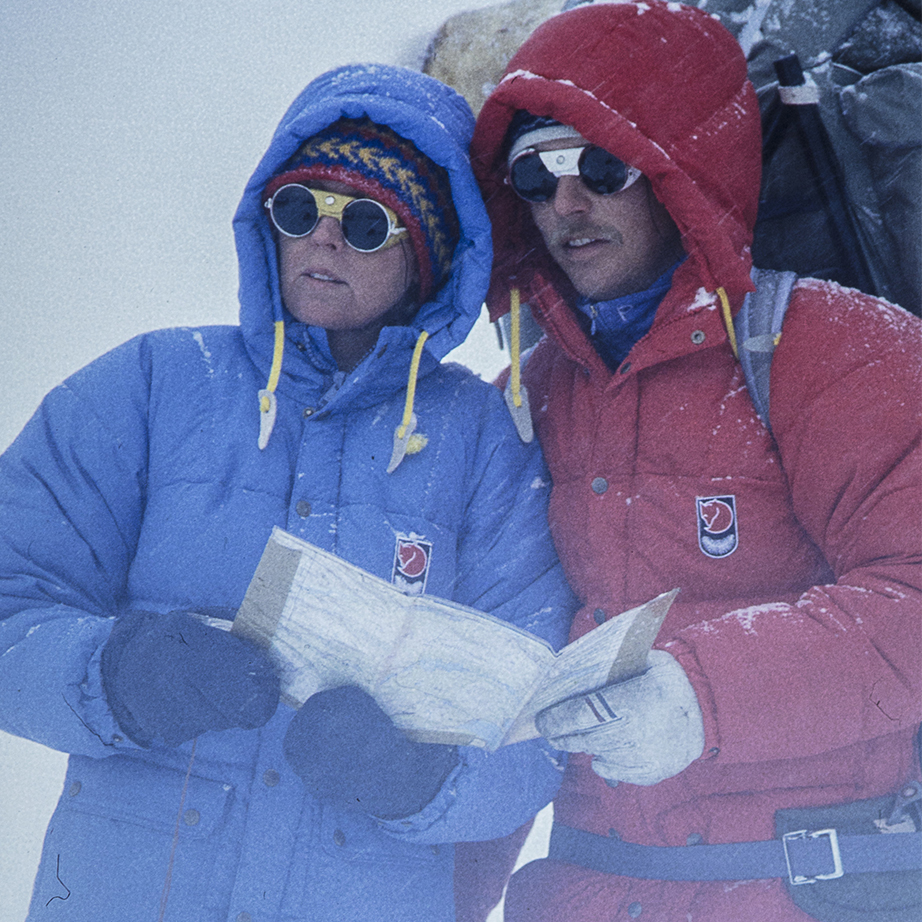

Over the years, the Fjällräven Expedition Down Jacket has been used by Swedish Polar Research Secretariat expeditions in the South Pole and Greenland. It has warmed sled dog drivers high in the Arctic Circle and rock climbers at Himalayan base camps.

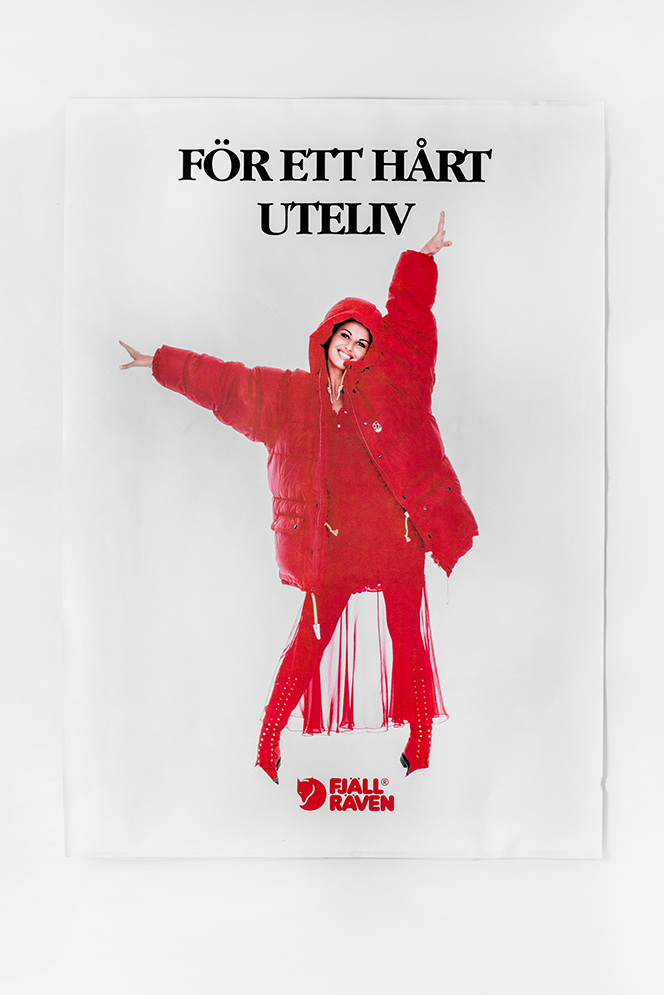

There was a time, though, when Fjällräven sold more Expedition Down Jackets in a fashionable district of Stockholm, than anywhere else.

It’s been said that the Swedish trend of down jackets has its roots in the hype surrounding the national skiing legend Ingmar Stenmark. The taciturn but unbeatable northerner popularised alpine skiing among Swedes, who had previously favoured the long-distance variety.

During their skiing holidays in the Alps, Swedish tourists copied the continental fashion on the slopes. This was the market into which the Expedition Down Jacket launched.

The jacket swiftly proved a hit with female consumers, who at that time favoured large jackets which covered their posteriors. But it wasn’t until well into the 1990s that the jacket gained traction beyond its inner circle of adventurers and outdoor enthusiasts. But when it did, its popularity quickly spread.

A career in the movies

Fjällräven’s warm down jacket was already popular with film industry professionals, especially among photographers who spent entire days shooting outdoors. When Jan Troell directed Flight of the Eagle, a drama about a famous ill-fated 19th century Swedish balloon expedition to the North Pole, he and his film crew kept warm in Fjällräven down jackets. It didn’t take long before other Swedish directors and film stars, including the actress Lena Olin, asked for the jackets too.

Extra, extra, extra small

For many women, however, the jacket’s outsize dimensions were a problem. Åke’s idea was that when you returned to base camp you could wear the jacket over your usual winter clothes, hence the generous proportions.

But this wasn’t necessarily what urban female consumers wanted at the start of the new millennium. A store in one of Stockholm’s more affluent districts asked Fjällräven for smaller sizes.

Åke was initially sceptical, knowing some of the functionality would be lost if the jacket didn’t cover the wearer’s bottom. But ultimately the company decided to listen to its customers and began to manufacture Expedition Down Jacket in sizes xxs and xxxs. Sales soared: by the mid-2000s, the jackets were being worn all over Stockholm.

Like many other successful branded products, the Fjällräven Expedition Down Jacket has been heavily pirated. During the run-up to Christmas in 2003, adverts in newspapers and on the Stockholm metro boasted cheap Fjällräven jackets up to 70 percent less than the retail price.

Fjällräven contacted the Swedish Enforcement Authority, which seized more than 1,000 pirated jackets imported from China. The fakes were destroyed and the importer was ordered to pay damages.

On 21 December, a court ruled that the Fjällräven Expedition Down Jacket was entitled to copyright law protection in the same manner as a pop song, book or work of art.

“Fashion doesn’t interest me”

So how did a Örnsköldsvik man become a key player in Swedish fashion?

When Åke was once asked this question, he bristled slightly. “Fashion doesn’t interest me. I’ve always done things because I need them myself. I’m not an exceptional type, I’m an ordinary person. And that means that when I make things for myself, they meet many other people’s needs.”

The key factor is simplicity. Åke hated being cold. So he designed a jacket that insulated against freezing temperatures better than any other on the market. He made it blue because blue is his favourite colour. He made the hood laces yellow because yellow and blue together reminded him of the Swedish flag. This bulky jacket has since been designated a work of art by a court of law – not a bad outcome for someone who simply wanted a garment to keep him warm.